11 Jul 2004

THE MOGHAMO MAN YESTERDAY-a chat with Pa Njei Thomas Mbah (Atabi) 1985.

In 1985 I prepared some questions and posed them to my late father and recorded them on tape. Most of the questions were pertaining to family history but as I listen to the tape today I realize that it revealed as much about the Moghamo man yesterday as it does about our own family.

My father died two years after this interview from natural causes according to medical records but as you will find out in the course of the discussion he believed that his stepbrother was the cause of his illness and eventual death. The typical Moghamo man is likely to believe in any cause of death other than that from natural causes.

Njei Thomas Mbah Njei Thomas Mbah

Servitude in Anong

My father’s dad (a polygamist) died when he and his five siblings from the same mother were still kids. The successor to his dad who was also chief of Kokum village (great grandfather of current chief) decided to use my father as security to obtain a loan from the traditional ruler of Anong village. In those days it was common practice to swap a person for a loan. The swapped person then had to labour for the creditor until the loan is repaid to secure his freedom. As my dad told me, in those days they had no notion of a calendar year as we understand it today. He neither knew precisely at what age he was swapped by the chief for a loan nor how long he was in servitude at Anong. From estimates we jointly made with him we came to the conclusion that he went to Anong at the age of 9-14 and spent between 6-10 years before his mother brought pressure to bear on the chief to go and bring him back to Kokum. According to him, his main occupation at Anong was rearing goats for the then Fon of Anong who was incidentally his maternal uncle. When asked whether he was treated differently from other children of Anong palace, he said no. He even went further to say that they jointly reared goats with the current Fon of Anong (at time of interview). The reason was because the Fon of Anong knew he was dealing with his sister’s child. From my calculation the probable calendar period of his stay at Anong could fall between 1910-1920.

Life with Big Brother

When my father returned from Anong, the chief of Kokum trained him how to tap white palm wine so that my dad could assist him whenever he was not around. During this period my dad was living with his elder brother from the same mother. His elder brother decided to go and snatch a married woman from Anong and keep as his wife. It should be recalled that it was common practice among the Moghamo men to snatch (‘shaa’ in Moghamo language) other people’s wives. It was a way of demonstrating their masculine prowess and superiority over the other man. This practice lasted into the sixties and it was common to see free for all fights (‘ndum’) breaking out in Guzang market linked to this practice. The procedure consisted of persuading a married woman and running away with her usually to your compound or out of Moghamo area if you felt vulnerable. Popular destinations out of Moghamo area included the CDC plantations of the South West province or Melong Area in Francophone Cameroon referred to as ‘France’. After successfully living with the snatched wife for a while, the new husband will then arrange to refund the pride price paid by the former husband through the father-in-law.

First Trip to the Coast

My father became a baby sitter for his brother’s only child named Endam. As a consequence of this he had to follow his senior brother to Kumba some 240 kms away from home. Back then, there was no motorable road linking Batibo and Kumba. The journey was usually made on foot and it could take up to a week to arrive your destination. According to him the foot track took them from Guka through Enyoh, Ewai and several other places I couldn’t recognize to Tinto Wire (Manyu), Manyemen, Nguti up to Kumba.

Later, a judgment rendered by the traditional authority ordered my dad’s brother to hand over his lone daughter to the wife’s former husband at Anong. The basis of this judgment was not explained to me by my dad. While in Kumba, my father did some manual labour with the British colonialists. According to him, he was a ‘carrier’ on the road project at Kumba station. The roads were dug with spades and hoes. While in Kumba, his mother sent a message for them to come home. Dad returned first followed by his brother. While at home his brother paid a visit to his in-laws at Anong. The brother returned from Anong and fell sick and died.

stem used for building

Second Trip to the Coast

Dad later returned to the South West province ( referred to as ‘Akop’) and went to work in a CDC rubber plantation at Mpundu. The working conditions in the plantation described by him were horrible. They lived in huts constructed with palm fronds (walls and roofs). They slept in crowded groups in those huts. Married people had to construct attachments to these hurts in order to safeguard their privacy. The boiling temperatures of this area and insect bites only helped to increase their woes. Supervisors in the plantation frequently used the cane on workers. My father belonged to the group of those labourers who did the tapping of rubber latex. Each labourer was expected to tap 50 trees a day and they were paid 10 shillings (about 110 Cfa francs) a month.

This is the type of seats of Moghamo fons of yesteryears. A demonstration by the late fon of Mbengog

Final Trip Back Home.

The nature of the work at Mbundu was enough to scare a daring young man and make him home sick. It was not however the pressure of the work that sent him packing from Mpundu but corporal punishment. According to him, his supervisor (incidentally another Moghamo man from Guzang) had him well thrashed with a cane for being slow at tapping rubber latex. He was further told in unmistakable language that if he doesn’t improve on his speed, he will have to send for his mother to come and take him after the next beating. The young man could not stand the humiliation and threats any longer so he called it quits. He was so touched by this incident that he could not wait for the salary at the end of the month and as such had to instruct a friend to collect it and send to him later. He then embarked on his one week trek back to Batibo.

Guzang market 2004

Starting an Independent Life in Batibo

Upon his return home, he discovered that the piece of farmland he had inherited from his late brother had been mortgaged (tighe) by the chief of Kokum to someone. According to the chief, he did that so that he could get money and pay tax to the colonial authorities. My dad had no choice but to look for money and reclaim his property from the chief’s creditor as the chief was in no position to cough out a penny. He had to work extra hard to catch up for lost time and unexpected expenses. He built a house at Mbekum (current farmland). The striking thing I learnt from him is that the currency in use in Batibo then were circular metal rings bigger and heavier than today’s wrist bangles.

These rings, I was told, were manufactured in Ogoja (Nigeria). I have tried to figure out how these currency manufacturers in Ogoja were regulating their money supply but the idea is too complex for my contemporary brain. It was certain that these metal rings, the British Sterling and trade by barter coexisted conveniently.

Marriage

It was common practice in those days to choose even an infant as a future wife provided the child’s father gives consent. The opinion of the child’s mother rarely counted. My dad’s future father-in law sent one Anwei from Kuneck to advertise his little daughter to viable men. My father reacted to the information and approached my mother’s dad at his residence in Bengang. He was accompanied on that mission by one Tigwere. The future in-law told them that the principal bride price was 400 rings excluding what his brothers will ask. They concluded that down payment will be 100 rings and the rest will come in installments of 50. My mother was still a child that had not certainly attained puberty. She was taken home by my dad and had to grow up in his house(I don’t know how many years) before attaining child bearing age. With assistance from his mother (a petty trader) my dad gradually paid off the bride price. I do not know how long it took him to complete the payment. When I inquired whether he remained with one wife till old age because he is a monogamist at heart? His reply was that it was due to limited material means. Yesterday’s Moghamo man was a polygamist and the number of wives one had played an important role in determining your social status.

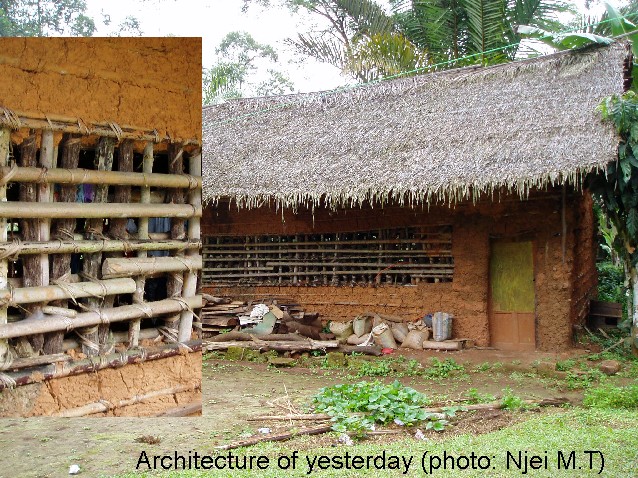

Housing

The construction of houses in those days was carried out with 100% local materials. The walls consisted of a matrix of sticks, bamboo and mud. The ceiling was usually raffia bamboo. The space in-between the ceiling and roof was usually a large store for firewood, grains and whatever needed to be kept dry by the smoke from the fire stand below. The roof frames were raffia bamboo and sticks held together by ropes pealed from the bark of fresh raffia bamboo. The roof was usually covered by thatches (carefully woven raffia bamboo leaves). The rapid degradation of thatches meant that the roof cover was renewed regularly esp. at the beginning of every rainy season.

The door shutters (windows were rare) were made of bamboo. The doors appeared like windows as they were usually small and one had to climb through them into the house. In those days, the ability of the child to climb into and out of the house was indication that the child was ripe for weaning. The house usually had the main section which served as kitchen/parlour/bedroom. A store or additional room existed in some of those houses. In polygamous homes, each wife had a separate house from those of her mates and husband. Typical household equipment consisted of bamboo beds, calabashes, wooden bowls and spoons, clear pots, jugs (weaved with spear grass) and bamboo chairs. Armed with an equipped house like this and a wife, the Moghamo man was ready to start making a family.

Food

The Moghamo man was quite democratic when it came to eating a wide variety of foods. The principal food then was cocoyams. Added to this were an array of eatables ranging from insects to wild fruits and vegetables. The free abundance of the weed used as vegetable called ‘ibang’ was quite memorable. Today, when a Moghamo man tells you that you have ‘harvested ibang’ it implies that you have obtained something for free. The Moghamo man ate and in some cases still eats tadpoles and frogs, crickets, some species of beatles and caterpillars, termites and a wide variety of leaves and animals. The domestic cat was and is still unfortunately both companion and food.

Specific historical questions

I asked my father to tell me a little bit of what he knew about lions. He confirmed that lions roamed in Moghamo area when they were young and that he knew of a specific case that involved lions devouring a child at Effa. As a precaution, he said people hardly moved in the forest alone and they usually avoided moving in the night. About his being a Presbyterian. He said he discovered the Presbyterian church at Bengang where church service was conducted in ‘Mungaka’ (the language of the Bali people). Prior to the coming of Christianity, the people of Kokum(our quarter) were worshiping a god near a spring called Nyereche. When asked how they felt when a road was constructed from Bamenda through Batibo to Mamfe. He said they were elated but he personally could not muster courage to enter a vehicle. He was too scared of the vehicle that he vowed never to board one. He was eventually forced to board his first vehicle by the police when he was required to go to Bamenda and testify in a case of suicide in the village. He had pleaded with the police to allow him trek from Batibo to Bamenda (40 kms) but the police turned down his request. After his compulsory first ride, he then fell in love with the motor vehicle. He never experienced combat during the various Bali ‘play’. He said they voted during the plebiscite to join East Cameroon for fear of Igbos (of Nigeria) who were very aggressive. He bemoaned the departure of the British pound which he described as ‘real money’. Does he believe there is witch craft and that people can transform into animals? Yes. He said people have talked about seeing animals that were caught in traps revealing their human faces so that they could be freed. He had never personally observed such an incident. About witch craft he said the weird character of some people suggests that they were not normal people. Besides, suspected witches were surgically opened by ‘traditional experts’ to reveal the witch craft lodged in their bellies when they die. Did unmarried young men use to have girl friends? Young people caught having pre marital sex were punished. The girl was usually beaten and the boy fined (usually required to give a pig). Adulterous relationship between bachelors and married women on one hand and married men and other people’s wives on the other was common but discrete. What happened if there was stalemate in a case brought to the traditional council? The litigants were sometimes taken to the bush to ‘catch a squirrel’. The procedure consisted of taking a number of people including the litigants and locating and surrounding the animal in its hideout, usually a hole. The animal is then flushed out of its hiding and everyone present will make maximum effort to catch it. If for example I have been accused by my neighbour for adultery and I insist I am innocent, the ability of the group to catch the squirrel with their bare hands will prove my guilt. If the squirrel manages to escape through the dragnet of the people that encircled it, I will be declared innocent. I inquired from my dad whom his best friend was? Mbabid Phillip (Free Boy) was the answer. His worst enemy? His elder step-brother (he died a couple of years before him). Witchcraft superstition in those days usually created enmity between brothers.

'ibang' a common wild vegetable eaten in the past

Bringing up children

When I asked my dad whether he had a figure in his head as to the number of children he intended to have. His answer was that one has to accept the number of children given to him by God. The issue of birth control was totally nonexistent in those days. The biggest problem he faced with some of us was ill health. My own complications were particularly worrisome. I was a born a stammerer and my stuttering was so severe that I can still recollect it now. In addition I had chronic bronchitis that lasted from about age 2 to about age 10. My stuttering was treated with a type of grass hopper that usually resided in pineapple plants. I ate the roasted insect when I was about 6 or 7 years of age and got well. The bronchitis never responded to any treatment until it stopped on its own. When asked who influenced him to send our elder brother (late Njei Mbah Wilfred) to school. His reply was that he was taken to school by other bigger children. Due to the proximity of our compound to Guka primary school (lone school in the area), parents from far away villages like Anong and Numben usually sent their children to come and live with my parents and attend school. It was some of these visiting children that persuaded my father to allow my late brother accompany them to school at a relatively young age. He was later to graduate from CPC Bali after untold financial sacrifice by our wretched family. After seeing the advantages of education, he then ensured that we, the younger ones went to school.

A memorable event

My late brother’s first job was with the agric department of the then West Cameroon. His first posting was to Befang in Menchum Division. One day he instructed labourers to clear and burn the bush around the office premises. In the course of doing that work, the fire accidentally burnt a lady’s hut. The matter was taken to court and my late brother and not the agric department was put on trial. My brother was sentenced to 9 months imprisonment or he pays a fine of 40,000 cfa francs. The poor civil servant did not have even a fourth of that amount and as such he was remanded in custody. When the news reached us, we were totally devastated and I can still recall how I wept. This was around 1966 or 1967. My father was particularly hurt by the lukewarm attitude displayed by his brothers towards this grave incident. He was expected to raise money within days for the fine or risk the son going to prison and ruining his career. He approached Mr. Phillip Mudoh (a carpenter by profession and father of Gideon Mudoh and others). Mr. Phillip helped him with a loan of 15000frs which he added to some money he got from a njangi. He then dispatched my mother to go and sort out the problem. My brother paid the fine, left the agric department and worked at Ndian with Pamol. He later returned to the agric department after higher authorities annulled the ridiculous judgment and compensated him.

.jpg)

wooden bowls

Sickness

Sometimes in 1968 or 1969 my father’s foot was afflicted by a form of cancer called Kaposi’s Sarcoma. It was a spherical growth and an untreatable sore at the same time. He was advised to consult some ‘traditional healers’. Each of the ‘medicine men’ approached, vowed that they would treat my father but every of them ended up talking about who must have caused the problem than finding a solution to it. The revelations from these ‘traditional doctors’ convinced my dad that his foot problem was caused by his elder stepbrother. According to them the senior brother planted some bad medicine and he stepped on it. The fact that the brother in question was suspected to be a witch further added credibility to this theory. By 1970 the situation of my father’s foot had degenerated to the point that death was imminent. At this juncture, medical opinion suggested that the leg should be amputated. My father vehemently refused amputation preferring death. Virtually everyone failed to pressure him except ebod Njong. This lady is the mother of Mrs Adeck nee Afuh Beatrice. The woman is so gifted with talent to give mature and convincing advice. She approached my father and told him to accept the amputation in the interest of the safety of his children. She told him that even if only his head stayed alive it will be okay as his open eyes will frighten the kites (witches) away from his chicks (children). My dad finally accepted the amputation which was carried out at Acha-Tugi Presbyterian hospital in 1970. He lived for 17 years after the amputation before dying from complications of cancer in 1987.

Conclusion

When I look back and try to reflect on how far we have evolved as a people in relation to our parents, an interesting picture emerges. Moghamo area has undergone one of the fastest transformations in specific arenas among other places in Cameroon. The changes that have occurred in the field of architecture, household equipment, hygiene , environment and nutrition have been quite dramatic. On the other hand, we have not made much progress when it comes to farming methods, superstition and death ceremonies. It is interesting how we embrace change selectively.

Copyright ( August 2001 by Njei Moses Timah

Njei Moses Timah [e-mail]

|